Following the many revisions of multicopters, I cannibalized the final revision for parts, and constructed a fixed-wing UAV. The objective now was sustained, long-range, autonomous-capable flight.

I was not able to pursue this project to completion, but in theory, the system was capable of those objectives (with minor changes) when I moved onto other things.

Project conclusion:

At the conclusion of this project, I had built a UAV capable of autonomous flight with full telemetry and video feedback from 2 CCD’s and one CMOS GoPro camera. Maximum range of these signals, when utilizing the high-gain motorized antenna system, was on the order of 7 miles. Though I never utilized it, the system was capable of automated or assisted take-off and landing, point-based loitering, and way-point flight path programming. Stall speed was slightly less than 35 knots, with top speeds over 70 knots. Altitude is legally restricted to 400ft AGL.

Early progress

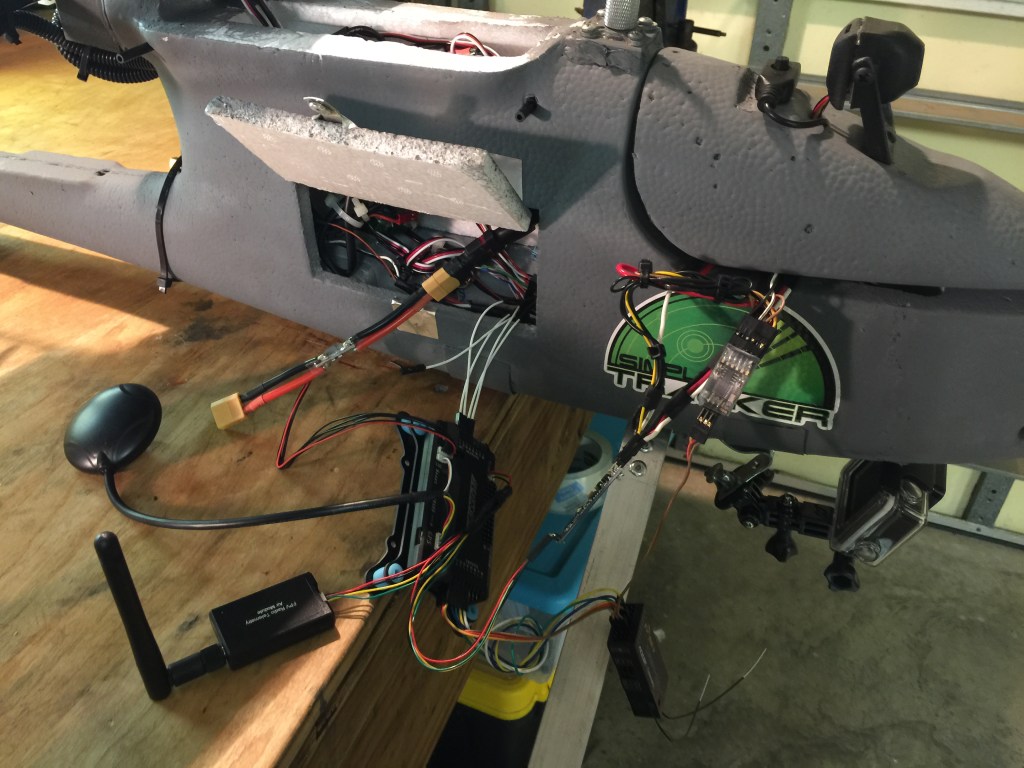

I purchased a kit, converted it to use dual motors spaced by a carbon-fiber rod, reinforced the tail with a fiberglass pole from a camping tent’s rainfly spar, and installed the electronics. I chose a basic Ardupilot system over Pixhawk, because there was a significant price difference in 2017 and the extra features were not necessary.

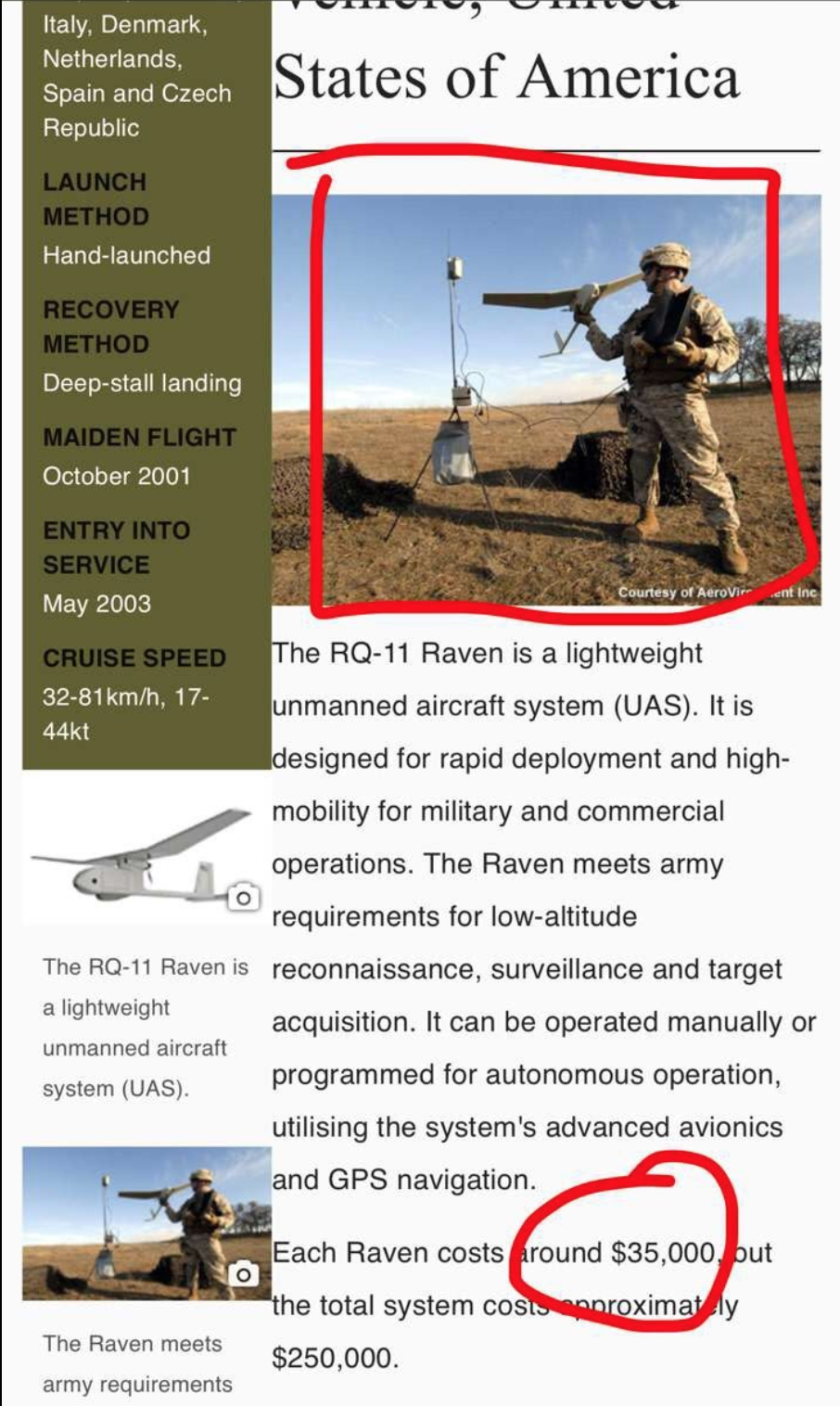

I noticed that this UAV was very similar to the RQ-11 Raven, marketed to the DOD/U.S. military. This was a motivating factor: the RQ-11 did not have auto-landing, lacked many features, but was priced at multiples of the cost of my system.

Once the drone was capable of flight, I developed landing gear, fine-tuned the flight-control systems, programmed controller macros, and tested the OSD’s telemetry feedback. The wings were labeled with the drone’s registration number, per the FAA’s newly-required ID requirement.

Antenna Tracking I – Long-range flight

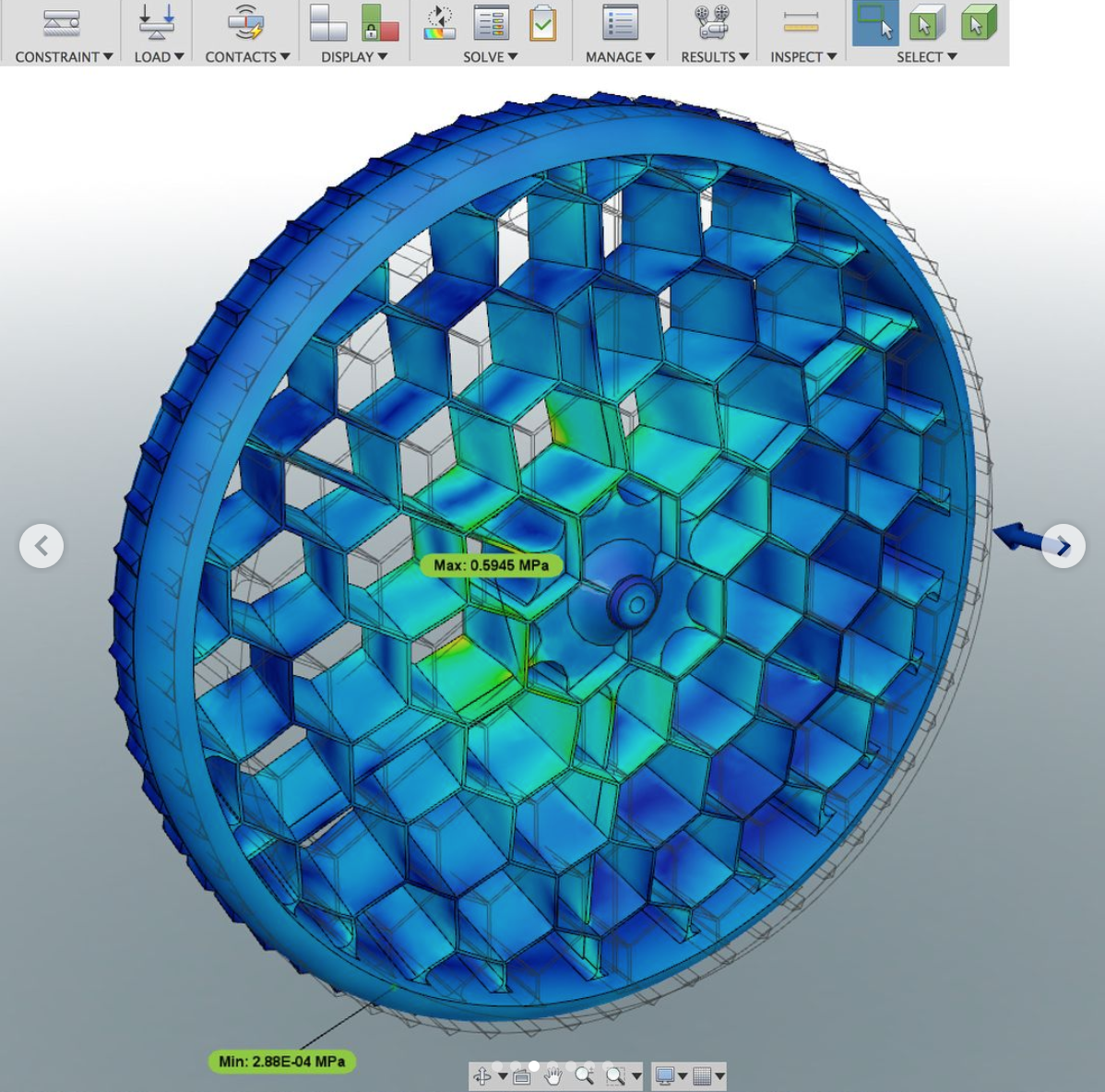

A key objective for this project was long-range flight. To do this effectively, both flight telemetry and a live video feed must be transmitted back to the UAV in real-time. Because the range of transmitted RF obeys the inverse-square law, it is much more efficient to utilize directional antennae, rather than omni-directional antennae (like circularly-polarized cloverleaf antennae).

The solution is, typically, to motorize a triplet of directional helical or patch antennae. The RSSI (received signal strength indicator) value of two opposing directional antennae is an input to an algorithm that rotates a central, high-gain antenna, seeking a heading that is coincident with the path of the UAV.

I initially built my own system, which did work, but did not perform adequately in the field:

The system utilized the scalar RSSI value from two analog video receivers (5.8 GHz), mapped to a range, and compared the values. If the difference was larger than a predetermined “dead zone” interval, an LED would light, and the stepper motor would turn.

Antenna Tracking II – Long-range flight

Because the home-built system did not perform in the field, I purchased a very similar system online. This breakout board came pre-loaded with a much better algorithm. It effectively tracked a heading with the strongest RSSI, and in effect, always pointed the high-gain antenna towards the UAV.

Telemetry and FPV

Safe long-range flight requires sufficient knowledge of onboard systems to make informed decisions about the flightpath. Onboard GPS, 2-way control with Ardupilot, and various other inputs (barometric data, voltage monitoring, current draw) are essential to a successful flight.

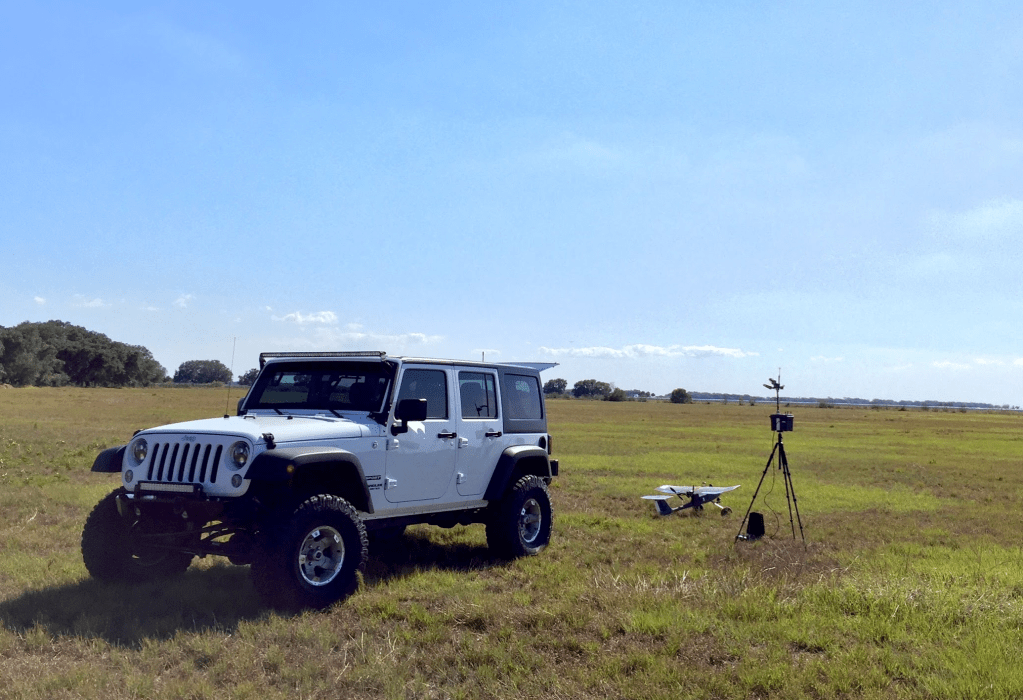

Final flights

Before moving onto other projects, I adjusted the pilot-assist functions, added flashing LED’s (driven by an Arduino Nano), and other minor things.